Many give up their careers in China because of low pay and few benefits

Nurse Song Yan would have sought a job in another country if not for her family and child.

"I work at least nine hours a day and overtime from time to time, and get meager pay," said the veteran nurse who has practiced the profession for at least 20 years.

"The working environment here is noisy, crowded and sometimes even chaotic," said Song, a senior nurse at the chest surgery department of Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University in Beijing.

For young nurses, the work is even tougher. "They usually have to work extra to gain patients' trust," she noted.

Many simply give up.

In some big departments with about 100 nurses, about 10 quit each year because the job is so physically and mentally demanding.

Some, usually younger ones, who have good command of a foreign language, have begun to go abroad for a decently paid nursing job, she said. "I have a family and a child to take care of, otherwise I'd also like to go."

Countries like Singapore, Japan and Saudi Arabia have begun to tap other countries for competent nurses because they cannot produce enough of their own to meet needs.

Singapore's healthcare system is expected to recruit about 1,000 to 2,000 foreign nurses annually to meet rising demand for healthcare prompted by a rapidly ageing population and China has become an outsourcing site of rising importance.

According to Lou Qinghong, manager of the Sino-US International Nurse Training Company, Chinese nurses are "newcomers" compared with nurses from English speaking countries such as the Philippines, Malaysia and India, which have been the first choices for international employers.

The agency based in Beijing helps train Chinese nurses for employers in other countries.

"Finding jobs abroad is becoming popular among Chinese nurses. Many nursing schools have opened English nursing courses, and many training agencies like us are promoting programs for Chinese nurses to work abroad," he said.

"Back when we started the business in 2005, we saw US employers come to Beijing to interview nurses and promise to help them and their family members get green cards as long as the nurse meets the qualifications to work there," Lou noted.

The frenzy declined after 2009, when the United States stopped issuing employment visas for foreign nurses whose academic qualifications were lower than a bachelor's degree, but Lou emphasized his agency's business is "stable" since the demand by hospitals in other countries such as Singapore and Saudi Arabia remains strong.

According to him, some Chinese nurses used working abroad as a "springboard" to finally settle down there.

Judy Duan, 33, said that when she was as a contract worker in a public hospital in Wuhan, Hubei province, from 2004 to 2007, her salary was less than 3,000 yuan ($490) a month, and her bonus and healthcare reimbursements were much lower than for "officially employed" colleagues.

In 2007, she passed the examination to become a registered nurse in Singapore and began to work there.

She worked in the long-term care unit in two hospitals and earned more than S$1,680 ($1,370) a month.

But challenges such as language accompanied the higher salary.

"Chinese nurses are very proficient in nursing skills. But Singaporeans speak English with a heavy accent. I also needed to communicate with co-workers from the Philippines, India and Myanmar," she said.

"Instead of Mandarin, many Chinese in Singapore speak Cantonese and Teochew dialects, which I found hard to understand," she noted.

In May 2010, she applied to immigrate to Canada, moved there with her family in March 2012, and is now applying to take an exam to become a registered nurse.

"Unlike in China and Singapore, a registered nurse here (in Canada) is a respected occupation and pays much more," she said.

Duan, who now lives in Ontario, considers herself lucky.

"I and my husband got permanent residency in Singapore in January 2008, whereas it got harder for my friends who later went to work there to obtain the status," she said.

"People came to Canada to work as nurses from around the world. Doctors and teachers emigrating from China are also willing to get a nursing degree and work as a nurse there if they don't find a job that suits them."

Stephanie Gu, 29, who is taking a nursing course in Melbourne, Australia, also finds herself accompanied by other aspiring Chinese students.

Upon graduating from medical school in Hebei province in 2006, she was chosen by a nursing agency in Beijing to work in a private hospital in Saudi Arabia for three years. At the end of 2009, she began to work in Singapore. Last year, she finally went to Australia to take a one-year nursing course at Deakin University, achieving her dream to work and live in a developed country.

Gu said she will become a registered nurse in Australia if she finishes the course and gets enough points at the IELTS exam, but finding a job as a nurse there is harder than before.

"Many Chinese nursing students came here to take the nursing course, for example from Peking University and the Capital Medical University," she said. "We all would like to settle here. But we have to compete with each other and many local would-be nurses, who may not be as proficient in clinical practice but speak much better English. I have seen so many cases of failure."

But she still wants to fight for the chance to stay.

"I work as a personal care assistant in a nursing home three times a week, each time for about five hours. My job is to take care of the daily lives of people living there. It's a lot of physical work and sometimes dirty, but I get A$19 ($19) an hour. It's a lot of money," she said.

"You can certainly make a living as a nurse in China, but not earn much money. It's harder if you want to buy a house and have children. Maybe I'll have to return, but I'll try to settle here," she said.

In recent years, Japan has been another country where Chinese agencies find booming business opportunities.

"Many agencies are introducing nurses to Japanese hospitals and other medical facilities," said a woman identified as Liu at the Sichuan Tianfu agency in Chengdu, Sichuan province.

Liu, who is in charge of the agency's program that introduces Chinese nurses to Japan, said this year it has introduced 15 nurses to the country, and it is planning to send at least another 15 there within the year.

"After going to Japan, nurses need to have language training courses and get the nurse certification there before officially working in a hospital. But they do part-time jobs in local hospitals to support themselves," she said.

The agency's website listed programs recruiting nurses for hospitals in Japanese cities and prefectures such as Nagoya, Osaka, Nara and Saitama. The introduction says "Japan now lacks 40,000 nurses" and nurses in Japan make "3 million to 4.2 million yen ($41,300) a year".

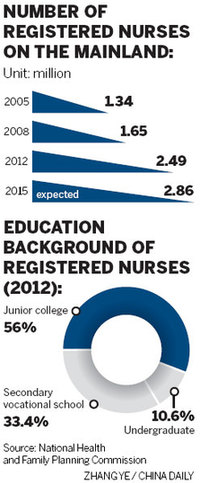

China had more than 2.49 million registered nurses last year, up 1.15 million over 2005, statistics from the National Health and Family Planning Commission showed.

Currently, China's doctor-nurse ratio stands at 1:1.5, far lower than the international average of 1:4.

The demand for nursing services is expected to increase as China's ongoing healthcare reform makes medical care services accessible to more people via an almost universal healthcare policy, according to Guo Yanhong, deputy director of the ministry's medical administration department.

"Thereafter, making the team stable is highly important," she said.

Besides the pay increase and favorable policies for nurses, more incentives like advanced training programs should be introduced to encourage good nurses and improve their working environment, she said.

Source: China Daily 05/13/2013 page1

新形态2020